The Gelati Mosaic is one of the most notable architectural elements of the Gelati Monastery, a remarkable medieval complex that once functioned as a cultural and educational hub.

The idea of decorating the Church of the Mother of God with a mosaic was conceived by King David “the Builder.” Creating an elaborate mosaic comparable to the legendary mosaics of Constantinople represented a bold challenge at the time. Initially, the altar was prepared for a fresco, but it was subsequently plastered to accommodate the mosaic commissioned by the king. In addition to the frescoes at Gelati, mosaic icons were also produced, with the icon of the Mother of God being the most notable example. Such an organic combination of mosaic and fresco is a rare occurrence, even in Byzantine cathedrals.

The Gelati Mosaic dates back to the period between 1125 and 1130. Notably, among the few surviving medieval Georgian mosaics, this particular example has retained its original appearance.

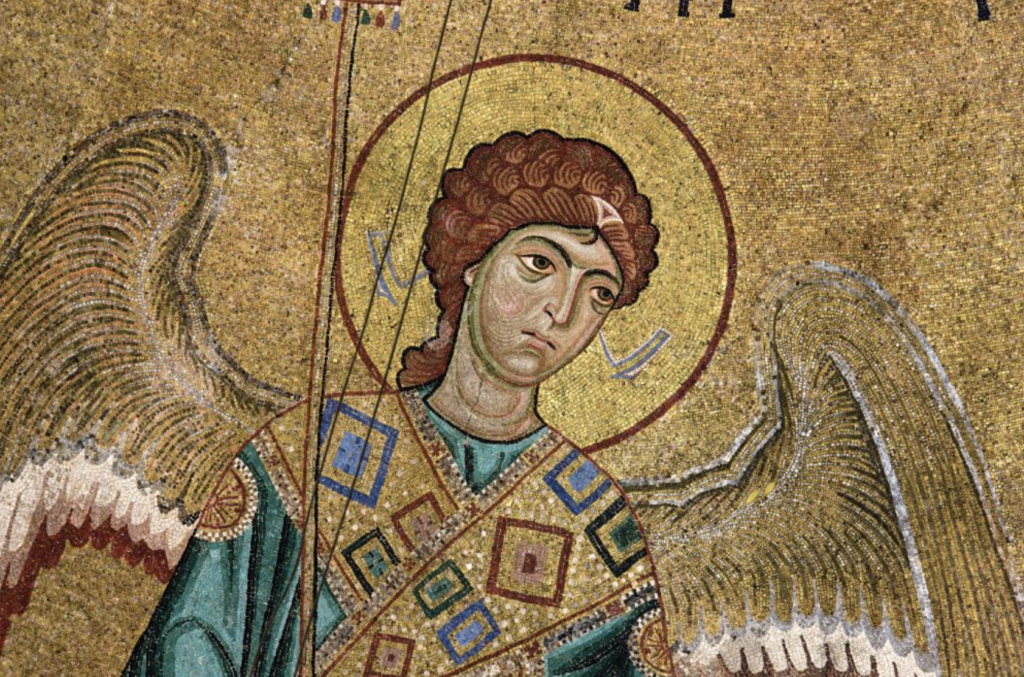

The Gelati Mosaic is situated on the vaulted roof of the apse in the main cathedral. The composition, depicted on a golden background, is solemn, monumental, and representative. It portrays the Virgin and Child seated on a richly decorated podium, flanked by archangels. Despite the relatively limited area of the scene within the cathedral’s vast interior, the significance of the images, their color palette, and the remarkable shimmer of the mosaic stones dominate the space. Collectively, these elements contribute to a spiritual atmosphere that seems to emanate from a divine source. During the celebration of the Eucharist, this atmosphere is further enhanced by the presence of other sacred objects.

While the height of the standing figures is nearly identical, the primary focus is on the central image of the Mother of God. This is further emphasized by the positioning of the archangels on the concave slope of the arch, which faces her. The Mother of God appears to emerge from the apse to assume her prominent position. Her figure is imposing, slightly offset from the center, which serves to soften the rigidity of the main axis of the composition. The face of the Mother of God was originally smaller in scale before the artist’s intervention, which resulted in a modification of its artistic contour. It was customary to accentuate the central figure with light; however, in this instance, the master employed light to highlight St. Gabriel, or more accurately, his head, while the figure of the Mother of God is distinguished by her color. The robe of the Mother of God is depicted in blue against a golden background, which is dark and dense in color, while the archangels’ robes are lighter in hue. St. Michael’s robe is a bright emerald, while St. Gabriel’s is a grayish ruby. White and silver are dispersed throughout the wings, appearing intermittently, with a series of golden feathers creating a radiant effect, thereby conveying a sense of lightness and animation.

In comparison to the aforementioned images, the Mother of God is depicted in a more “earthly” manner. The master differentiates between the figures of the Mother of God and the archangels, offering an artistic approach that aligns with the functional role of the archangels. The initial design of Gabriel the Archangel’s head underwent modification, with the introduction of a slight tilt that imbues the image with a sense of gentleness. The concentration of light above the saint’s head serves to highlight his body and underscore his role as a “kind messenger.” Michael the Archangel, frequently designated as the “head of the celestial cavalry” and the “punishing angel,” is depicted distinctly. His countenance is characterized by a somber and austere expression, a dark complexion, and downturned corners of his mouth. The differentiation among the archangels imbues the overall scheme with heightened emotional resonance, a quality typically absent in other representations where they are depicted as indistinguishable figures. The Mother of God’s face is marked by watery eyes that emit a luminous warmth, a gesture that evokes poignant lyricism. This emotional expression strikes a harmonious balance with the monumentality and strength that are hallmarks of Gelatian images, evoking the grandeur of Georgian painting.